The List Family Murders 50 Years Ago

"Mild-mannered" John List massacred his wife, three teenaged children and aged mother in New Jersey on November 9, 1971 -- and disappeared into a new identity for 18 years

Patricia List, was a pretty, spirited high school girl whose deeply religious father murdered her, her two teenaged brothers, her mother and her grandmother on November 9, 1971, a day of horror in their ramshackle mansion in New Jersey. Pat would be 66 years old today, 50 years later. She would have been eligible for Social Security now, and it’s possible she might have been near the end of a career in the theater, as her friends and teachers assumed she would have — an avocation her father cited as one of the reasons for killing her because the theater to him represented sexual license.

The John List family massacre continues to horrify a half-century later mostly because of the savage nature of the crimes and the smug rationalizations the killer later offered for his dreadful actions. But also central to the fascination is the fact that after he spent that day murdering his family one by one in Westfield, New Jersey, John Emil List disappeared seemingly into thin air. He moved out West, assumed a new identity, and was not finally caught till 1989, eighteen years later.

In 1990, I published “Death Sentence: The Inside Story of the John list Murders,” a detailed account of the crimes and their circumstances. I had worked hard to report the book, and I considered it to be a modest entry in the honorable genre of literary true-crime narrative. Alas, the book merely elicited a snotty notice in the New York Times Book Review by one Beverly Lowry, who opined that I was “neither a graceful writer nor a fabulously insightful one.” Lowry, herself a writer of remarkably tedious true-crime books, did at least allow that Sharkey “gets the job done.”

Nevertheless, “Death Sentence” continued to sell for all of these years, and it was very nicely republished in 2018 in an updated new edition by Open Road. It continues to sell respectably. Here’s the Amazon listing for the 2018 edition.

Here’s the story of “Death Sentence” as I wrote it:

***

Below: List, Helen, and their teenage children

John Emil List was by outward appearances a mild-mannered accountant and family man. He was a World War II veteran, almost stereotypical of that generation in post-war America – suburban, conformist, concerned about social appearances, upwardly mobile, married with children. He was also devoutly religious as a member of the conservative Lutheran Missouri Synod that he had grown up within, in Bay City, Michigan.

During the late 1960s, he moved with his wife, elderly mother (she had supplied the down-payment) and three teenage children from the Midwest to a ramshackle 19-room Victorian mansion in Westfield, a comfortable middle-class town in New Jersey 25 miles from New York City. In Westfield, he became increasingly politicized against the ongoing national sexual and cultural revolution, which he saw reflected in his sixteen-year-old daughter Patricia and her intense interest in pursuing a career in the theater, an avocation he regarded as sinful. He also resented his by-now sickly wife, Helen, for her disregard of the church and for what he regarded as her libertine ways. She drank too much and liked socializing with other people. She was lusty. Men liked her.

Below: The List house in Westfield, New Jersey

In 1970, List was fired from his job as an minor marketing executive with a New Jersey bank (the reason: nobody at the bank liked him). Debts piled up. By the fall of 1971 a bank was seeking to foreclose on the house. Patricia was increasingly involved with her high school friends in a community theater club. He suspected the girl was a drug user, which was not the case. The anti-Vietnam war movement was still raging. Pat had a tightly fitting a tee-shirt with a peace symbol on it. She sometimes talked back when he objected to her friends and her social attitudes.

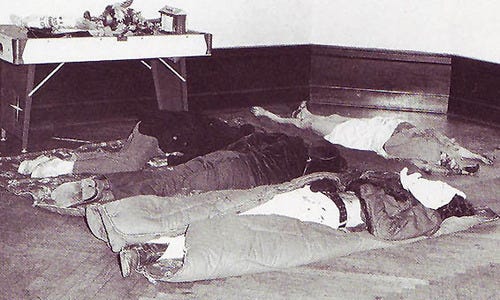

List finally decided to wipe his slate clean. After careful planning, he shot to death his wife, his three teenage children and his mother, one by one, over the course of that November day in 1971. He arranged Helen’s and the children’s bodies on old sleeping bags beside each other on the floor of the mansion’s unfurnished ballroom, and left his mother’s body sprawled on the floor of her room upstairs. He sat down to write a long, self-serving letter that he left for his pastor, in which he asserted that he had massacred the wife and children in order to save their souls from eternal damnation, not to mention the shame of imminent destitution. He added that he killed his elderly mother to spare her the anguish of seeing what he had done.

During that day, he called the children’s schools saying that a relative in the South had died, and they’d be out of classes for several weeks. Late in the gloomy afternoon he prayed, made himself dinner, had a good night’s sleep, got up the next morning and turned on lights throughout the house. He turned down the thermostat, put the radio on loud to WQXR, the New York Times’s classical music station out of New York, grabbed a suitcase -- and disappeared into thin air.

Here it got creepier. As weeks went by, Patricia’s high school friends in the community theater club became more anxious, especially a few close friends to whom the girl had confided her fears that her father had warned that she had better have a pure soul, as he was going to kill her and her brothers. Finally, desperate, the kids and their drama teacher, a nervous theater-buff and frustrated opera singer named Ed Illiano, went to the house one cold night, entered through a broken back door – and found the horrible scene in the ballroom. The bodies had been there for almost a month. There was no sign of John List – except for the handwritten manifesto he left for his pastor on the kitchen table. The police arrived. The crime scene became chaotic.

Below: The bodies of Helen List and the children as they were found in the house nearly a month after the murders. The body of List’s mother, Alma, was on the floor upstairs.

After the murders almost a month earlier, the fleeing List had parked his car at Kennedy Airport In New York to throw police off, but then scuttled into Manhattan, where he took a train westward and drifted to Denver as the police and FBI searches to find the fugitive went nowhere

By the winter of 1971 and early 1972, the outlines of the killer had slowly begun to emerge in Denver, like a photograph gradually developing in a tray. Bit by bit, List reinvented himself as Robert Clark, a widower who, like so many others, had drifted out West in the 1970s for a new start in place where a man with a past could get himself resettled, few questions asked. Where nobody knew your name.

He started out living in a tiny trailer near a Holiday Inn on the Interstate. There he got a job as a kitchen helper, and then a cook. In time, he found work as an accountant, then reinserted himself into a Denver church of the Lutheran Missouri Synod, the same conservative sect he had grown up within in Michigan, and belonged to in New Jersey. In a Bible class he met a divorced, anxious middle-aged woman named Delores, and eventually persuaded her to marry him. Having few choices in life, she did.

They moved into a condo unit, where the next-door neighbor, Wanda Flanery, an Irish-American woman in her sixties who later described herself to me as an “old busybody,” became friendly with Delores but disliked and distrusted her humorless, prissy husband.

Two things happened to get Wanda’s attention in 1987 and 1989. Wanda was an inveterate reader of sensationalist supermarket weekly tabloids, which she bought for amusement. One of them, the Weekly World News, published in 1987 a routine feature story back on page 24 about the long-enduring mystery of the List murders in New Jersey, with photos of the murdered family, including List himself. As Wanda was reading this with casual interest, she happened to glance out her window and saw her neighbor “Robert Clark” taking out the trash. Shocked, she recognized him as an older version of the man in the newspaper photo. She reviewed her impressions of Robert Clark’s unpleasant characteristics and concluded that they matched the description of the unpleasant family-murderer John List in the newspaper story.

Aghast, Wanda approached Delores quietly and nervously shared her suspicions, worried that her friend might be in danger, but Delores scoffed and told her she was imagining things. Wanda lived alone and was fearful, so she retreated in silence. A year later, “Robert Clark” and Delores moved cross-country to a new job he had got as an accountant in a small firm in Virginia. Wanda occasionally stayed in touch with Delores by mail.

Meanwhile, back in Westfield, New Jersey, a couple of younger local cops who had grown up fascinated by the John List murders and disappearance took notice of a popular new tabloid TV show, “America’s Most Wanted,” and decided to pitch the List story to it. Initially resistant because the case was so old, the TV producers finally acquiesced and hired Frank Bender, a forensic sculptor from Philadelphia known for doing police work, to create a bust model of what John List presumably would look like 18 years after the crimes.

When the program aired in May 1989, Wanda watched it in Denver with her daughter and son in-law. Actually, Wanda told me, she decided that the sculptor’s bust didn’t look very much like the man she knew as Robert Clark, but her son-in-law pressed her to call the phone number, because a reward was offered. Afraid she would be making a fool of herself, she agreed.

Hundreds of calls came in with false reports of John List sightings, but Wanda’s was among those that seemed to be worth looking into. FBI agents followed up and John List was identified and arrested in Midlothian, Virginia. He was tried and convicted in New Jersey of the five murders.

It never came out at the trial that the bodies and the crime scene were initially found by high school kids who knew something was desperately wrong, when the town police had not been interested in the importuning by the kids and their adult drama teacher’s that Pat List and her siblings had been missing for far too long, and the cops and schools ought to be looking into why.

List died in prison in 2008. While he was serving his five life sentences, he was befriended by an ex-CIA agent, a fellow World War II veteran named Austin Goodrich, who helped the imprisoned List compose a self-published memoir in which List referred to his murdered family as “collateral damage” attributable to his own purported Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in the war -- though as I found out in the military records, his “combat” experience had actually been very slight in the final month of the war in Germany. In that self-pitying memoir, List described his hours of cold-blooded executing a death sentence against his wife, children and mother in November 1971 as “my day of infamy.” He referred to his massacring his family merely as “the tragedy.”

Here are some of the take-aways I identified as I looked deeply into the life and personality of John Emil List and his crimes:

--Greed and 1950-60s social climbing. List, an insecure “mama’s boy,” felt incredibly entitled all his life, but lacked the necessary skills, judgment and personality to insert himself into the upper middle class where he saw himself as rightfully belonging. His greed for social status and its related accoutrements drove him all of his adult life.

--Rage against a secularizing culture of the 1960s and the breakdown in authority as he saw it, represented by the youthful antiwar movement and epitomized by his distress over the emerging sexuality and independence of his 16-year-old daughter Patricia as she started to come of age in the New Jersey suburbs of New York City. Every time Pat List walked in the front door, the furies of the 1960s and early 1970s blew in with her, he believed. As List’s daughter matured through high school, her mother Helen, herself nostalgic for youth and freedom she had lost in her miserable marriage, increasingly was seen by List as being in unholy alignment with the teenaged daughter.

--Cunning. List carefully planned mass murder and disappeared into a new identify that he managed to maintain for almost two decades. His relocation to the West was in some ways representative of a restlessness in American society in the 1970s, when many were looking for a fresh start – and able to find it, no questions asked, in the West. This was really the last time in America that someone could disappear as easily.

--Police ineptitude. That crime scene in Westfield after the small-town cops finally arrived was an unprofessional mess, with local reporters wandering through and the police anxious to obfuscate the fact that the bodies were actually found by high school kids angry that the local cops were not following up on the mystery of their missing friend.. The FBI subsequently failed in attempts to track down the fugitive, being wary of looking for him in a specific religious setting where his patterns suggested he would most likely be found. At the trial, a good defense lawyer would have at least been able to plead for a mistrial, given the police mishandling of the crime scene, though of course List’s confession letter was indisputable.

--Arrogance. While in prison, List subsequently cynically justified his savage crimes. Essentially, he blamed his brief war service in World War II in that self-righteous memoir written in 2006 with the collaboration of another cynical man of List’s generation, a bitter former CIA agent and a publicity hound. The co-author was a veteran of the CIA’s bad old days, who shared John List’s resentment of the way the world had turned out, but who had joined him in one last-ditch effort for fame. That agent, Austin Goodrich, is now dead.

At the murder trial in New Jersey in 1990, List was represented by a Union County public defender, Elijah Miller, who made an attempt to rationalize his pitiful client’s day of horrors. “My client was clearly out of step with the times,” Miller told the jury. On November 9, 1971, steeped in “Old World values,” aghast at the social upheavals roiling America, battered by severe personal and money troubles, fearful of what the future held for his children, “his whole world was crumbling,” Miller claimed. “On that fateful day, he slipped from despair into oblivion, and entered hell with his eyes open. For the salvation of his family, he acted as he did.”

I never bought into that religious salvation baloney, though some media do to this day. In the 2018 epilogue to the updated edition of “Death Sentence,” my 1990 book on the List story, I expressed disdain for List’s phony rationalizations and pious excuses. which I believe were an insult to any actual combat veteran suffering from real PTSD.

I ended my new epilogue in the revised “Death Sentence” (published by Open Road) by quoting a comment by the great Chitlin’ Circuit comedian Moms Mabley, who was speaking about the death of a man she had once known and loathed: “They say you shouldn’t say nothin’ about the dead except good. He’s dead? Good!

Nobody came forward to claim his body after John Emil List died in a New Jersey prison on March 21, 2008. No one mourned his death.

Good.

##